Elsewhere on this blog, I've tried to tell the story of the White and Cox families, and how most of them left the Huntingdonshire villages that their forebears had lived in for generations, to start new lives in London, Stoke and Nottingham.

In this post, I want to tell the story of how one of the Cox children, John George Cox, chose to leave the village of Woodhurst for the growing railway town of Swindon. This time, I will also explore one generation further to show how that migration went even further for his daughter - to the other side of the Atlantic Ocean and, tragically, to the bottom of it as well.

The railway comes to Swindon

There is a good choice of books, online posts and even museums explaining how the Great Western Railway transformed the Wiltshire market town of Swindon into a railway town. In summary, its Chief Engineer Brunel and his associate Daniel Gooch recommended Swindon as the site for the GWR's central repair works. Construction started in 1841 and in a few years the works were operational.

By 1851 the works were employing over 2,000 people, both repairing and building locomotives, and later both rails and rolling stock. A model 'railway village' was also built providing not only housing for the workforce but also a hospital, school, sports ground and library. Further expansion then took place, with the construction of more housing, shops and, by all accounts, a good number of pubs too! A town with a population of less than 5,000 people in 1851 grew to over 50,000 residents by 1911.

The development took place around the railway line, which ran to the north of the original market town, so that "New Swindon" grew up a mile or so north of "Old Swindon".

|

| New and Old Swindon - and the GWR Works - 1885 |

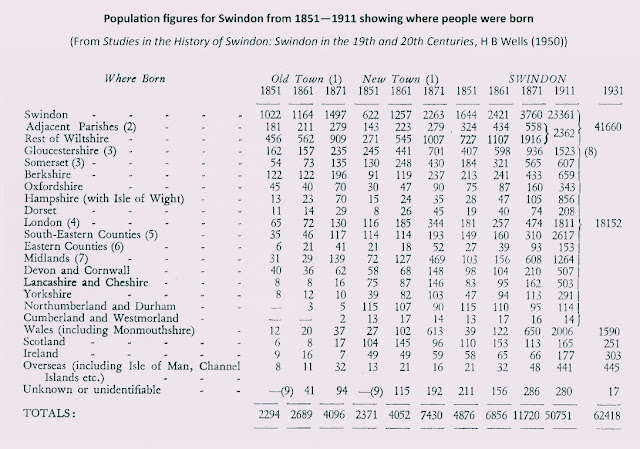

Internal Migration into SwindonThis table of population figures shows how quickly the population grew, but also analyses where those new residents were originally born:

As well as people moving into the town from the rest of Wiltshire and surrounding counties like Gloucestershire, Somerset and Berkshire, there were significant influxes from other areas too, notably London and the South-Eastern 'Home' Counties. Workers from Wales also came to Swindon, particularly to work in the iron rolling mills. It's noticeable that John George Cox's birthplace of Huntingdonshire, listed in the table amongst the 'Eastern Counties (6)', makes one of the lowest contributions to the population changes. So what inspired John George to choose Swindon, when other parts of the family chose elsewhere?John George and Mary Ann make a good choice

Whatever gave John George Cox the idea to head south-west, from Woodhurst to Swindon, his life story suggests it proved to be a good choice to make. It is quite possible that someone in his extended family alerted him to the employment prospects that were becoming available in the town. For example, his aunts Susan and Martha Ann, and their contacts with the GWR through employees like Thomas Singer and Robert Pratt, may well have been able to advise John George to head in that direction.

The table below shows that he may not have set out for Swindon alone, because the first proven record of John being in the town is his marriage to Mary Ann Elliott in 1878. Mary Ann, also originally from a Huntingdonshire village, may well have met John George in St.Ives, where they are both recorded as living in the 1871 census. It's also possible that John George's younger brother, Fred, also made the journey, because the 1881 census lists him as boarding in the same house as the newly married couple. However, after that date, there are no further confirmed records showing what became of Fred:

Swindon may have been a railway town but it seems that John George chose not to work directly in the rail industry itself. Instead, he worked as a tailor and draper.  |

| John George Cox, tailor, in the 1898 Kelly's Directory listings for New Swindon |

No doubt, there were thousands of potential clients willing to part with some of their railway-related earnings to pay for the work of a good tailor. The census records showing John George's progress through the trade, from a "cutter" in 1881 to having retired as a "master tailor" by 1911, suggest he was good at his trade.

|

| The 1911 census record for 1, Hunt Street, Swindon |

The addresses perhaps also give an indication of the family's growing affluence. Brunel Street, their 1881 address, was one of the terraced streets built in the 1860s to house the new workforce. Regent Street, their address in 1891 and 1901, was one of the roads developed in the centre of New Swindon for shops. Their 1911 address, Hunt Street, was a later development that apparently include 'elaborate brick terraces dated 1895'. No.1 Hunt Street, where the family lived, is certainly large enough to be a guest house today. These, and some of the other addresses mentioned in the family records, are shown on the map below:

Obituary and Probate confirm John George Cox's success

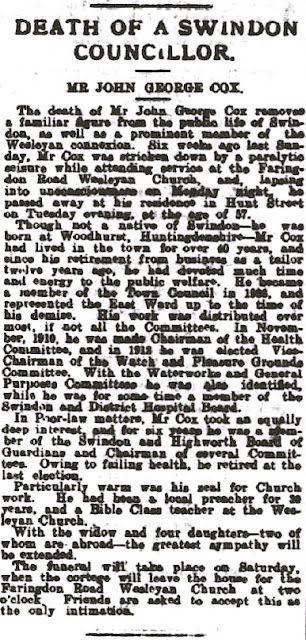

An obituary in the Evening Swindon Advertiser of 28 May 1913 shows just how successfully John George Cox had taken to life in his newly adopted town:

DEATH OF A SWINDON COUNCILLOR

MR JOHN GEORGE COX

"The death of Mr John George Cox removes a familiar figure from the public life of Swindon, as well as a prominent member of the Wesleyan connexion".

So, amongst other positions, Councillor John George Cox had been Chairman of the Health Committee and Vice-Chairman of the Watch and Pleasure Grounds Committee, as well as being a member of the local Board of Guardians.

It's not made clear whether John George had an overt party political affiliation, although his support may have arisen primarily through his "Wesleyan connexion". As a local history explains: "Until after the First World War there was but little relationship between national party politics and the affairs of the borough council ... rival groups existed, but these represented local interests rather than national party divisions. The G.W.R. was naturally strongly represented and a minority opposition soon arose. The nonconformist churches, too, which had a strong following in the town in the later 19th century, put up their own candidates. Before the end of the century candidates were also sponsored by both the Conservative Party and the Swindon and District Trades Council, which soon after its formation in 1891 revealed an affinity with the Independent Labour Party".

The article reveals that John George "had been a local preacher for 30 years, and a Bible Class teacher at the Wesleyan Church". The connection makes sense given the Cox family's non-conformist roots in Huntingdonshire. Just as his sisters' marriages in London had been registered at the Denbigh Road Wesleyan Chapel in Notting Hill, the marriages of his daughters were registered at the Farringdon Street Wesley Chapel in Swindon (although, perhaps just as noteworthy, all three of the bridegrooms are railway workers!)

As further evidence that moving to Swindon had worked out well for John George Cox and his family, the probate records show that when he died, on 27 May 1913, John George was able to leave £4474 - equivalent to over £500,000 now - to his two (then) married daughters, Ethel and Maud:The daughters of John George and Mary Ann John George and Mary Ann had four daughters. The records above show that Frances became a school teacher, while both Ethel and Violet are listed in the 1911 census as being "milliners" before they marry, initially following their father into the clothing trade. Maud's census records simply states "none" under occupation.

The ancestry records show that Ethel sadly dies before she is forty, in Swindon in 1920, whereas Violet lives on until 1970. I have not traced any further records for their mother, Mary Ann, nor for the oldest daughter, Frances. It could be that she is one of the two daughters described as being 'abroad' at the time of their father's death in the obituary above. What's certain, is that the other daughter who is overseas at this time is Maud Gertrude Cox, living, as unexpected as it may seem, with her husband, Frederick Chirgwin ... in Cuba!

Like John George Cox, Frederick Chirgwin's father, Richard, had moved to Swindon from another county, in his case Cornwall, but in order to to work directly for the Great Western Railway itself. The GWR records show that his employment in the Swindon Works Locomotive Department began in 1878 and that by 1883 he had been promoted to foreman:

His son, Frederick, had been born in the town in 1882 and had started work with the GWR in 1897. The company records show that him as a clerk at the Swindon Stores Department from 1901 until he resigns and is paid up to 24th October 1909 - apparently to leave for warmer climes in Cuba!

The first evidence for Frederick's new employment comes from the passenger list of the SS Adriatic, arriving in New York on 3rd November 1909 from Southampton. On board are two men from Swindon employed in "railways" - Frederick Chirgwin and Joseph Williams - headed for Sagua La Grande in Cuba.

Then, on 3rd August 1912, the passenger list for the merchant ship Corcovado lists an 'engineer' Frederic Chirgwin, arriving at Plymouth from Havana, Cuba:

The ship appears to be returning just in time for the wedding of Frederick and Maud on 21st August 1912, registered in the Wesleyan Chapel records above. Presumably, the husband and bride, both in their late twenties at the time of the marriage, had already known each other for some time, both being born and brought up in Swindon.

The newly married couple don't stay in England together for long, however, because by 17th October 1912 they are arriving in New York, having left Southampton on the SS St. Paul eight days earlier. The passenger lists again record the final destination as being Sagua La Grande, Cuba, but also adds that Frederick is working as a 'clerk' for the Cuban Central Railway Company:

Working for Cuban Central Railways

How exactly Frederick - and presumably Joseph Williams - had been offered a position in Cuba is not known. Presumably news of job opportunities overseas became known in the railway town of Swindon and Frederick took up that opportunity, apparently to become "Assistant Stores Superintendent" in the Cuban sugar-cane town of Sagua La Grande.

Railway expansion had of course been taking place across the globe. In Cuba, construction under a colonial Spanish regime, and through a collection of competing private enterprises, had been haphazard. One of the main drivers was the need to transport sugar cane. However, increasingly both the capital and the skilled workforce - like Frederick Chirgwin - came from abroad, predominantly from the United States and Britain. As one researcher explains, "In 1875, all public railroads were still owned by Cuban companies; towards 1900, some 70% of the capital invested was British".

After the Spanish-American war of 1898 gave the US economic dominance over the island, railway companies operating in Cuba attracted further overseas investment, including into the British-owned 'Cuban Central Railways Company' running the railway network in the sugar-cane growing areas around Sagua La Grande:

|

| Investment Opportunities into Cuban Central Railways - 1901 and 1907 |

As the 1913 map below shows, Cuban Central Railways (lines in blue) operated the network around the commercial centre of Sagua La Grande, and out to its port of Concha. This was clearly a good place for the Company to have its stores - and to have an experienced young clerk like Frederick Chirgwin helping to manage them:

Maud returns to England in 1913, and then again in 1915

Maud's father's obituary tells how John George Cox had suddenly fallen victim to a seizure, dying six weeks later, in May 1913. It seems that Maud therefore took the decision to leave her husband and return home for the funeral as there are passenger records of Maud returning home to England, alone, in June 1913, returning once more to Sagua La Grande in October:

In September 1914, the couple had their first child, a boy who they named Richard. The next year, 1915, they arranged for Maud to travel to England again on holiday, and to take the infant boy to see his extended family. According to Peter Kelly, another researcher into their family records (see below), the plan had been for Frederick to follow some time afterwards on another crossing. However, after seeing Maud and their son off from Cuba in April, Frederick would never see either of them alive again.

Lost on the Lusitania

The Chirgwins had taken the fateful decision to book Maud and the infant Richard into a second class cabin on the Lusitania, which sailed from New York for Liverpool in 1st May 1915. On 7th May, just off the coast of Ireland, the ship was torpedoed by a German submarine. A second explosion soon followed, possibly caused by munitions being carried on board, and the ship took just eighteen minutes to sink beneath the waves.

There are many detailed books and online resources about the sinking of the Lusitania. One of the best places to read further is the "Lusitania Resource" and I am indebted to one of its researchers, Peter Kelly, for information he has provided for this section of the post.

The resource explains that "of the known 1,960 verified people on board Lusitania, 1,193 perished. This number includes the 3 stowaways arrested after the ship left New York. An additional 4 people died of trauma related to the sinking shortly afterwards, bringing the total lost to 1,197". Amongst the list of victims on the website, can be found Maud and Richard Chirgwin:

The infant's body was never found but, chillingly, the number "88" against Maud's name is her "body number". As Peter Kelly has explained to me, the "lower numbers were those who died on board the lifeboats on route to Queenstown [now Cobh] and those who died on shore shortly after landing. There were three temporary mortuaries established to deal with the remains of the bodies recovered. As the days passed, and bodies were recovered and brought ashore by naval and fishing vessels, they were numbered as they were landed. As far as Maud Chirgwin is concerned, it is likely that her body was recovered on the 7th or 8th May, but I have no definitive details as to whether she died on a lifeboat or on shore after being landed, although this is the most likely scenario"

Maud's body was identified and then buried on 10th May 1915 in Mass Grave C, 5th Row, Upper Tier, one of the three mass graves dug at the Old Church cemetery, outside Cobh, County Cork:

Frederick Chirgwin after the loss of his wife and child

Peter Kelly's research has established that Frederick's father, Richard, travelled to Ireland as soon as it became clear that Maud and the infant Richard had not been found alive. The Evening Swindon Advertiser for 13th May carried this report: 'Amid the many distressing scenes which Mr Chirgwin witnessed in Queenstown, the most painful was that when, after inquiring at the offices of the Cunard Line, he was directed to an adjacent yard where some 40 or 50 bodies were lying. "I could not attempt to describe the scene" said Mr Chirgwin to our representative.'

Maud's father-in-law was unable to identify a body and neither was her husband, Frederick, when he was later shown a photograph of the body identified as belonging to Maud. However, a ring and brooch found on the body was felt sufficient to establish that it was indeed hers.

|

| North Wilts Herald 14.5.15 |

The passenger list for the SS Havana shows that the grieving Frederick was able to book a voyage from Havana to New York, arriving there on 20th July 1915. From there he transferred to the Cunard Line's 'Orduna' and arrived in Liverpool on 31st July. (It's worth noting that the 'friend' listed as Frederick's contact in Cuba is none other than Joseph Williams, presumably the same railwayman he had originally left England with on the SS Adriatic in 1909. Other records suggest that Joseph may be the husband of Frederick's sister, Emily - but that would be another investigation!)

What was the effect on Frederick of the loss of his wife and child through the attack on the Lusitania? Some of those emotions would have been, understandably, anger and the wish for revenge. According to Peter Kelly, "on his return to England, Frederick Chirgwin applied to The Commissions Board offering his services to the Army as an officer. His letter stated: 'My Lord, I beg to make application for a commission in the Army Ordnance Corps ... I say that I have strong and personal reasons for making this application as my wife and only child, who were coming home to England for a holiday, were lost on the Lusitania. Immediately the news reached me I relinquished what was a highly lucrative post and came to England in order to offer myself in whatever branch of the service I could be most useful'.

Peter Kelly's research suggests that Frederick was indeed granted that commission and was promoted to the rank of Major. The military records that I have found support that claim, but also suggest that he may have still been in the Royal Army Ordnance Corps (RAOC) as late as March 1920, as part of the "British Military Mission" in South Russia - the failed attempt to bolster Denikin's "White Army" in the Civil War that followed the 1917 Russian Revolution.

After leaving the army, Frederick remarried - in New York in 1921 - and went back to working for railway firms in Central and North America. As two final bits of evidence from passenger lists, here's Frederick listed as a "Railroad Executive" on a ship sailing from Guatemala to New York in 1934 ...

... as well as Frederick listed - on a 1937 crossing being made by his second wife, Edna - as working for "International Railways of Central America, Guatemala".

The IRCA - and its parent company after 1936, the United Fruit Company, owned the railway lines connecting both Guatemala and El Salvador to the Caribbean. The United Fruit Company withdrew its ownership following the post-WW2 Guatemalan Revolution. Frederick and Edna will have lived a much more comfortable life than the lives lived by many of those who suffered under the United Fruit Company - but Frederick's probate record, when he dies near Dartford in 1955, leaves £5182 - not that extravagant an amount - to be passed on to Edna.

***

And that ends the tale of how the Cox family, originally labourers and carpenters from a small Huntingdonshire village, went in search of work to London, Stoke, Swindon, and even to Cuba and Guatemala - but how, for Maud Gertrude Cox, her life was cut short, as it was for many others of course, by World War.

Comments

Post a Comment