In my previous post, I traced the history of the Swift family, one of the roots of my family tree, up until the middle of the nineteenth-century. It was a family that had established itself through the butcher's trade on the Isle of Sheppey, in Kent.

I found out how, despite him nearly being made bankrupt, the trade was being successfully maintained in the village of Eastchurch by Thomas Crayden Swift, my 3rd great-grandfather. At the same time, he was also growing a family that eventually totalled fifteen children, through three successive marriages.

In this post I trace the second half of Thomas' long life, highlight some stories from the lives of his eight sons, and show how many of them took on his butcher's trade in their working lives (leaving the seven daughters for a separate post - largely to keep the story a little shorter!)

|

| Thomas Crayden and Edward Crayden Swift's grave - and a mystery additional name on the gravestone |

Plotting the lives of father and sons

After 1840, the UK census records - alongside other sources like marriage banns, burial records, electoral registers and trade directories - allow a picture of the lives of Thomas Crayden Swift and his eight sons to be mapped out.

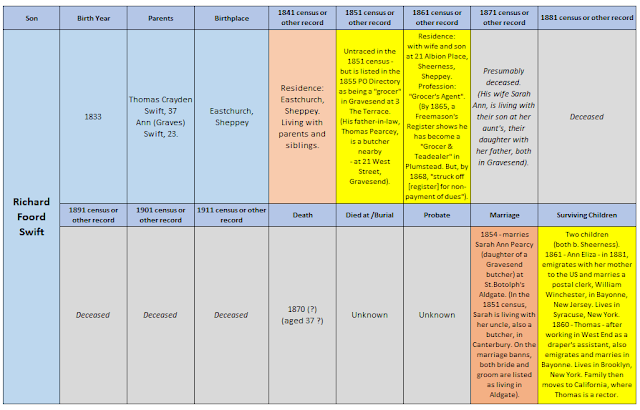

The chart below (magnified in sections later) shows how many of the sons followed their father's trade - and how many of their sons also did the same. This is done by highlighting where the profession "butcher" is mentioned in orange:

As the chart shows, six of the eight sons became butchers. Whether coincidence or not, the two that didn't, John Crayden (a carpenter) and Richard Foord (a grocer), died the earliest! However, Richard Foord did marry the daughter of a butcher - as did Samuel Crayden (one of the six butchers). The six 'butcher' sons were able to take the specific skills and knowledge they had learned from their father in Eastchurch to build lives for themselves feeding the growing populace of London. However, only a handful of their children continued in the butcher's trade - although one that did, Edward James Swift, son of James Cozens Swift, became my great-grandfather.

Twelve tales about their lives

Each of the lives of the father and sons - and their families - has stories to tell. I have picked out something of interest from each of them:

1) Thomas Crayden Swift - not just content with the meat trade

It seems that Thomas Crayden Swift wasn't content just with the meat trade. He may have lived to be a very old man for the nineteenth century, but he also looks to have been someone looking to the 'new' as a way to make a living.

In the 1841 census, Thomas is listed as a "butcher", as expected. However, by the time Bagshaw's 1847 Kent Directory is published, he doesn't only appear in the listings for Eastchurch as a butcher but, in addition, as a registrar as well. (A separate listing for a 'Thos. Swift' as a butcher in Minster-in-Sheppey is probably his second son, Thomas, rather than being a second premises for Thomas Crayden Swift) :

To take on the post of 'registrar' in the 1840s means that Thomas Crayden Swift was definitely looking for the latest 'career opportunities', because the General Register Office - setting up a national system of civil registration, rather than relying on parish records - had only been set up in 1837. But that's not his only new post!

His other new avenue of employment was to take charge of a Post Office. There are two records of him being appointed by the Postal Service in Eastchurch, one in May 1845 and another in February 1853, his name in both records listed alongside alongside others appointed from across Britain and Ireland:

The 1845 record, where Thomas is described as a butcher, may be appointing him as the "receiver of letters" as they arrive from Queenborough. The 1853 record, marked "Eastchurch, Sittingbourne" may be confirmation of Thomas running a Sub Post Office in the village - Sittingbourne perhaps being the nearest town that letters were transported to/from. But, again, Thomas Crayden Swift is taking advantage of newly created opportunities.

While the General Post Office had been in existence since 1660, the introduction of the 'Penny Black' stamp in 1840, followed by legislation that eventually extended postal delivery to every household in England by 1900, was bringing about the kind of modern postal service seen today (although who knows whether it will still exist tomorrow under a privatised, cost-cutting Royal Mail ...).

The number of post offices had more than doubled from around 4000 in 1840 to nearly 10,000 by 1854. For Eastchurch to have a Sub Post Office is an indication of the pace of change - and with Thomas Crayden Swift taking his opportunity to be part of it. His two different trades are recorded in the 1858 Melville's Directory:

|

| Melville's 1858 Directory and Kelly's 1862 Directory for Eastchurch |

Although still listed just as "Butcher" in the 1861 census, the 1862 Kelly's Directory for Kent (above) confirms just how many different Eastchurch pies Thomas Crayden Swift had his fingers in ... he's the village's butcher, receiver of letters at the Post Office, and the Registrar of Births, Deaths and Marriages. He must have known most people's news as well!

As it had been in 1832, Thomas Crayden Swift's occupation of property was sufficient to entitle him to vote in the 1868 General Election. Alongside virtually every other registered voter in the parish (remember, there was no secret vote...) , the poll book again shows him backing the two Conservative candidates, Pemberton (P) and Milles (M) - who were both elected to Westminster for the Eastern Kent constituency:

2) Thomas Crayden Swift - retiring to London, buried in Brompton Cemetery

The 1871 census is the first one that records Thomas Crayden Swift as living in London, instead of Eastchurch. Listed now as a "Retired Butcher" it looks that he has chosen to leave the Isle of Sheppey and follow his sons and daughters to London. He is living on Balham Road, Streatham, South London, with his wife, Ann, their daughter, Frances Mary Swift - a governess - and a grand-daughter, Annie Bretnall, as well as a domestic servant:

By the 1881 census, Thomas Crayden Swift is now an 85-year-old widower, listed for the first time without a profession against his name. He has outlived three wives and five of his sons. He is still listed as the head of the household and is now living with three of his daughters, Sarah Sands, Susanna and Eleanor, along with Eleanor's husband and their three children, at 47 Barnsdale Road, Paddington.

By 1886, he has died, with his last address provided on the burial record as being 24 Stonefield Street, Islington. He is buried, as a 'Dissenter', in Brompton Cemetery, Kensington and Chelsea, on 22 February 1886, aged 91. He is listed as the 'third internment' in the plot, being buried alongside his wife Ann, who died in 1880, also at Barnsdale Road, the 'second internment'. But who was the 'first internment?'

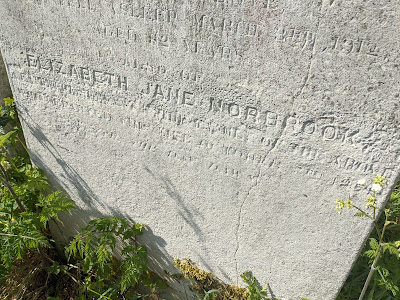

Mysteriously, the first name recorded on the Brompton Cemetery register as being buried in the plot is not any of their sons or daughters. Instead, "Elizabeth Jane Norbrook" is listed as the first internment in the grave. But who is she?

The burial register shows that she died at the age of 20, and was buried on 7th October 1878. Her last address is given as 86 Gloucester Road, South Kensington, with the gravestone describing her as "a faithful servant of the family of the above". The address suggests a possible link with the life of Edward Crayden Swift - the fourth and final internment in the grave in 1912 - as is described below.

|

| The grave where all four are buried |

3) John Crayden Swift - keeping it in the family

The census records across the whole Swift family show the close links between brothers and sisters, and across different generations too. Adult siblings are sometimes living in the same household, and grandchildren, nephews and older parents are also sometimes listed too. In some cases the links are also made across families, with two Swift siblings marrying two siblings from another family.

In John Crayden Swift's case, the links are not so obvious - because his only surviving detailed record is of his marriage in 1840 to Henrietta Mary Spiers, the daughter of a Thames waterman, George Spiers. He then dies in 1846.

Instead, the links across families are shown through their children's marriages. Their son and daughter, John George and Susannah Foord Swift, end up marrying another sister-brother pair, Sophia and John Cole. So how did these two pairs of siblings become two married couples? The ancestry records provide some clues:

John Crayden Swift's marriage record shows that he must have left the Isle of Sheppey and moved further up the Thames to become a carpenter in the town of Gravesend, where the Spiers family were also based:

Three years after John Crayden Swift's death, Henrietta remarries Edward Travis, a wheelwright, and moves across the Thames to Grays in Essex. The 1851 census therefore shows her two children, John George and Susannah, living in Grays with Henrietta Mary and Edward:

Meanwhile, John and Sophia Cole are listed together as brother and sister in a separate census record from 1851, this one from a mariner's family in Queenborough, on the Isle of Sheppey. John is a "sailmaker's apprentice":

The next clue comes from the 1861 census which shows that John Cole had moved to Grays, where he is listed in the 1861 census as a sailmaker, boarding at 198 High Street. But, a glance on the next page shows that the boarder at 200 High Street is none other than George Spiers, Henrietta's father! This may have proved to be a good way to be introduced to his grand-daughter, Susannah Foord, because, by 1866 they have married, their marriage registered in the Orsett district that then covered Grays.

Perhaps Sophia Cole then got to know John George Swift , because they then married in 1867, although in Wandsworth. In the 1871 census, they are living with their first two children in the nearby Essex village of Stanford-le-Hope. Interestingly, John George seems to be trying his hand at being a hairdresser, although he returns to being a carpenter in later census records!

In the same census, John and Susannah Foord Cole are living as husband and wife in Argent Street, Grays, and Henrietta and Edward Travis are living nearby in Grays too. All three couples live the rest of the lives in this same corner of Essex.

4) Thomas Swift - the first to leave home to be a butcher elsewhere

Like his older brother John Crayden, Thomas Swift had left the Isle of Sheppey by the time of the 1841 census. However, unlike his older brother, he stuck to his father's trade.

In the census record he is listed as a "butcher J", a journeyman butcher. The head of his household is a Thomas Saunders, "Butcher", presumably Thomas' employer. They are living in Palace Street, by the cathedral, right in the heart of Canterbury:

As the 1847 Bagshaw's Directory pictured higher in the post shows, a Thomas Swift is by then running a butcher's shop in Minster-on-Sheppey. This may well be Thomas (junior), having returned to Sheppey to run a business of his own, because he is also recorded as marrying Mary Bigg, a local farmer's daughter, in Minster in July 1844.

Their first two children are certainly born in Minster around this time although they may have also briefly lived in Beddington, Croydon, as this is where the birth of their third child, Elizabeth, is registered in early 1851.

By March 1851, when the next UK census is recorded, Thomas, Mary and their first three children are living in the heart of another city - London. Thomas is, as expected, listed as a butcher. Their 1851 address, Somerset Street, Aldgate, is now called Mansell Street. It ran next to the site of an old East India Company warehouse that was being converted into the Haydon Square Goods railway depot around this time:

Their next daughter, Louisa is probably born here, as her birth was registered in the City of London in 1853, but the family appear to have moved to Islington soon after as Mary dies there in 1855. The widowed Thomas - still a butcher - is recorded as living in City Gardens, Islington in the 1871 census where he then dies in 1875. His trade is even recorded on his probate record, where he leaves "effects under £100" to be administered by his daughter Elizabeth:

As a London butcher, Thomas Swift fared better than some who endured the poverty to be found in Victorian London, but he certainly didn't make his fortune. None of his children follow, or marry into, the same trade. However, as we shall see below, some of his younger siblings fared better again.

5) William Swift - the son who stayed at home to help his father

William was the son who stayed in Eastchurch to work with his father, long after all of the others had left the Isle of Sheppey:

In the 1861 census, William, already 40, is still listed as living in his father's household, together with Ann, his father's third wife, and five of their daughters. His trade is listed as being a butcher. It's not hard to imagine that William and his father have formed a close bond, working together in the family trade.

Only in 1864 - when his father must have been finally at the point of retiring from the butcher's trade - does William marry, have children and then follow his brothers into London. But who does he marry? Just as with the Coles and Swifts above, the records show this is another case of two pairs of brothers and sisters forming two married couples.

William (44) marries Mary Jacob (38), the daughter of Thomas Jacob, the farmer of Skeet Farm, situated between Stowting and Lyminge, to the south of Canterbury, Kent. (The families may have had some prior links because Stowting is also the burial place of Thomas Crayden Swift's second wife, Susannah):

|

| From the 1876 Ordnance Survey maps of Kent |

But one of Mary Jacob's older brothers, Frederick, has already married William's younger sister, Mary Ann Swift. In fact, the wedding took place 13 years earlier, on 7th November 1851, in Stowting. However, as I shall show in another post, the couple had soon after emigrated to the United States, settling in Iowa. In fact, while William was marrying Mary in 1864, Frederick was fighting for the Iowa infantry in the American Civil War!

After their marriage, William and Mary don't travel quite so far ... just to Lee, now part of Lewisham, in South-East London! The birth records of their five children (including John who is untraced after the 1881 census) all show that they are born in 'Lee, Kent', between 1865 and 1872.

|

| The census record for the family in 1881 |

But why Lewisham? The answer may be another family link. His younger brother, James Cozens Swift, had already made the journey ahead of him to try his luck at the butcher's trade here. In both the 1861 and 1871 census records, James Cozens is listed as a butcher living with his family in the area - in 1861 in Boone Street, Lee, and in 1871 in a newly built street by Lewisham station, Thurston Road. So, when William arrives with his family to be a butcher in Lewisham, his younger brother is already there working in the same trade.

The 1871 census lists William's family as living at what appears to be 'Watson Place', Lee - although I cannot trace any such street name. However, the White Horse pub listed in the same street (now operating as the Lewisham Tavern), was later given the address of 1 Lee High Road, close to today's central Lewisham:

However, and perhaps after James Cozens Swift dies in 1878 (see below), William and Mary decide to move to North London. The 1881 census record (above) shows the family living in Bulls Lane - now known as Church Lane - in Finchley, with William listed, once again, as a butcher, as he is in later censuses too.

William and Mary settle in Finchley, moving to a premises on The Broadway, Church End, and then, after retirement, living nearby on Long Lane. When William dies in 1908, the probate records again show that, while the butcher's trade fared them well, William also didn't make a fortune either. He leaves £115 to his widow Mary:

The census records suggest that his two sons may have continued in their father and grandfather's trade, certainly Frederick who is recorded in the 1939 census as being a "Retired Butcher" living in Stoke Newington.

6) James Cozens Swift - a Lewisham connection that I never knew existed

For much of the long time that I spent working and living in the London Borough of Lewisham, I was totally unaware that my great great grandfather, James Cozens Swift, had lived there long before me. He was buried in Ladywell Cemetery in 1878, a cemetery that I had driven past many times, although (my London-based family tells me!) there seems to be no obvious remains of his grave left today.

|

| The entrance to Ladywell Cemetery - where James Cozens Swift is buried |

As explained above, James Cozens Swift was the first of the brothers to move from the Isle of Sheppey to the Lewisham area to be a butcher, to be followed there later by his older brother William.

It appears that James had already left his family household as early as the 1841 census, as (see above) he is not listed amongst his siblings then living in Eastchurch with his parents.

It's not clear where he was residing in 1841, however, I have traced a 'James Swift' from the 'Isle of Sheppy' in the 1851 census at the home of 'butcher and farmer' William Mills in Chislehurst, Kent (now in the London Borough of Bromley). His profession is listed as "servant", but not "house servant", so he may well be working as some kind of butcher's assistant.

The address in the census is given, rather imprecisely, as "South Side of the Village of Footscray". The Kent PO Directory for 1851 also lists William Mills as a butcher and farmer in Foots Cray, one of four "highly respectable villages" (which may not be how the Crays would necessarily be described any more!).

It's also in Chislehurst that James Cozens Swift is married, on 23rd February 1853, to Caroline Elizabeth Powell:

From there, as also shown above, James Cozens and Caroline must shortly move to Lee/Lewisham, as their five children are born there between 1856 and 1865 (although their fourth child, George, baptised at St.Margaret's Lee in 1861, only lives for a few weeks).

|

| The Swifts at 26 Boone Street, Lee, in 1861 |

As described above under the story of William Swift, James Cozens Swift is listed as a butcher living with his family in Boone Street, Lee, in 1861 - and then in a newly built street by Lewisham station, Thurston Road, in 1871. While both streets still exist today, sadly the homes that are listed in the census records do not. James, however, does not appear in any further census records, as he dies at the start of 1878, at the age of 51, and is buried in Ladywell Cemetery on 17 January.

Did any of his children continue into the butcher's trade? In the case of his son - and my great-grandfather - Edward James Swift, I know that he did from tales that I heard first-hand from my old Aunt Gwen. She told me that it was in his work as a butcher's assistant that he met Harriet White, my great-grandmother, in the Mayfair hotels where she was a cook.

|

| My great-grandparents marriage in St.Stephen's, Lewisham, in 1878 |

His chosen trade is confirmed by both their 1878 marriage certificate and by the 1871 census record where 15 year old Edward is listed as living with his uncle, Samuel Crayden Swift. Both uncle and nephew are listed as butchers. One of the witnesses at their wedding, Edward's sister Susannah Swift also later marries another butcher, William Woolgar (see below), so the links with the butcher's trade continued here too.

Finally, there's no probate record that I can find for James Cozens Swift - although my family history can vouch that there was certainly no great fortune passed down to his children! It proved to be two of his younger brothers that fared best of all.

7) Caroline Powell - before and after James Cozens Swift

As James Cozens Swift's wife, Caroline Powell, was my great great grandmother, it's only right that one of these twelve stories should be about her life and ancestry - especially as it has a few interesting tales to tell. (The 'Powell' name, however, is purely coincidental - it has no connection to the

Powell in my surname today).

A full history of Caroline's ancestry would be too long a tale but, as the picture below tries to summarise, it's an ancestry that threads back from London to yet another county - this time Sussex - and from fathers with a different trade - shoemakers (in one record, even given the old name 'cordwainer').

Once again, records survive going back to the eighteenth century. They include: ancestors who have to make their mark, rather than write their name, on marriage record; a death certificate giving 'dropsy' as the cause of death; and a collection of West Sussex villages - finishing up with Caroline living with her parents in 1841 in "Beach, Littlehampton".

Just as so many others in my family tree left their home towns and villages for London, Caroline left Littlehampton for the city, and is shown in the 1851 census working as a 23 year-old housemaid in a surgeon's household in Barking, East London. How she ended up meeting James Cozens Swift and marrying him in Chislehurst in 1853 is not known but, as set out above, she did so, and the census records then show the couple living together with their children in the Lewisham area in 1861 and 1871.

The 1871 census shows James Cozens and Caroline living at 68 Thurston Road, Lewisham, with their three daughters, Susannah, Caroline and Eleanor. But there are two others listed too - widower Robert Read, a commercial traveller from Bermondsey, and his sister, another Susannah.

There's a great added detail in the 1861 census which lists Robert Read as a "Commercial Traveller (Biscuits)" - while there's no proven connection, it would be interesting to know if he had contacts with

Peek, Frean & Co. Ltd, which started trading in the area in 1857 - soon to turn it into "Biscuit Town".

By the 1881 census, James Cozens has died, so Caroline has remarried. But the record shows that her new husband is none other than the 'biscuit-seller', Robert Read!

In fact, Robert had now changed trade to become a "Clerk, Seed Merchants" in Reading. He is listed as living there in Donnington Road, alongside Caroline and her two remaining daughters, Susannah and Caroline. (Eleanor is now a servant in Ealing and will shortly emigrate to Canterbury, New Zealand - as will Caroline, to Queensland, Australia).

Fast forward to the 1891 census and Robert and Caroline, now Read, are living at the home of daughter Susannah in West Wickham, Bromley. She is now Susannah Woolgar as she married 'journeyman butcher' William Woolgar in Reading in 1887:

The census record also lists William and Susannah's first two children 'Edgar Cozens' - showing Susannah's father's name was still being remembered - and 'Eleanor Florence'. Eleanor is born in West Wickham but the baptism record at St.Mark's Deptford shows that they went for a joint ceremony with Susannah's brother Edward James Swift, on 3rd June 1888. The other child being baptised was another Eleanor - and she was my grandmother!

Just to complete the story, Caroline dies soon after the 1891 census and Robert four years later, his death recorded as being in 'Bromley, Kent'. Sadly, Susannah has also died there in 1894, aged only 36. However, in one last quirk of the family tree, William Woolgar lives on until he is 78 with his probate record showing that he dies at "Middle House, Dorking Road, Epsom"

But Middle House, Epsom - once the workhouse - was then also an infirmary. In 1948 it was to become part of the new NHS as Epsom District Hospital ... and in 1963, that's where I was born.

8) Edward Crayden Swift - the mystery of the "faithful servant"

A quick look at the table for the fifth son, Edward Crayden Swift, shows that he spent his life as a butcher, never marrying and having no children. But the census records - and the £546 13s that the probate records show he left to his sister, Susanna(h), (over £70,000 in today's prices) - show he was able to live well out of his trade.

Edward Crayden Swift may well have moved to London in the 1850s - certainly, at least at the time of the 1861 census, he is working as a butcher in the Paddington area. By 1871 he had already become a "butcher employing four men" - presumably the four journeymen also listed in the census record:

His home is very much a home for his extended family too, however. The four other names in the 1871 census record are his sisters Susannah and Eleanor, Richard Bennetts - Eleanor's fiancée, and his nephew, two year old Frank Bretnall, the son of Elizabeth - another of his sisters. In later census records, as presumably his trade brings in good earnings, his household also contains domestic servants as well as butcher's assistants plus, in 1891, an apprentice book-keeper too.

Perhaps part of the secret of his success is his address throughout that period - No.9 - and then No.5 - Gloucester Road, Kensington. This whole area was being developed in the 1860s in an expensive 'Italianate' style. So, it looks like Edward Crayden Swift had found premises in a wealthy part of the city, a good place to run a butcher's shop.

|

| The Gloucester Road area from the 1869 OS map |

Edward Crayden Swift retires - now to live with his sister Susanna(h) again - to an Edwardian apartment block - 105 Loraine Gardens in what is now Widdenham Road, Holloway, N7 - where he also dies in 1912.

The burial register at Old Brompton cemetery shows that Edward becomes the fourth and final internment in his father's grave plot. But, as mentioned above, is it Edward's shop in Gloucester Road that also provides some clue to the identity of the mystery "first internment" in the grave - Elizabeth Jane Norbrook the "faithful servant of the family of the above" who died at 86 Gloucester Road in 1878?

There's a reasonable possibility that she is Jane Elizabeth Norbrook - as that is how her death is separately registered - who was baptised in Chertsey, Surrey, in 1858. However, there is no further clue as to how her life ended and why she was given a burial - and an epitaph - on the Crayden Swift gravestone.

9) Samuel Crayden Swift - working in the heart of Dickensian London

The summary table for the sixth son, Samuel Crayden Swift, also shows that he spent his life as a butcher, and had no children - although he did marry in 1859, to the daughter of another butcher. He died in 1877 at the age of 47, so younger than most of his brothers. However, the probate records suggest he left a little less than £1,500 to his wife Mary census records - around £200,000 in today's prices. He died living in a property in Fitzrovia and had purchased a plot in the Old Brompton Cemetery. So, of of all the brothers, Samuel Crayden Swift seems to have made the most out of the butcher's trade.

However, life for Samuel Crayden Swift hadn't always been in genteel surroundings. In 1851, the census records show that he is living as a "butcher's man" in the heart of Clare Market, then a maze of crowded lanes near Lincoln's Inn Fields, written about by Dickens in books like The Old Curiosity Shop. He may have learned his trade from his father in Eastchurch, but this must have been where he really cut his teeth.

What the area was like when Samuel was working there can be gleaned from this account by

Peter Cunningham in his 'Handbook of London', published in 1850: "

There are about 26 butchers in and about Clare Market, who slaughter from 350 to 400 sheep weekly in the market, stalls and cellars. There is one place only in which bullocks are slaughtered. The number killed is from 50 to 60 weekly, but considerably more in winter, amounting occasionally to 200".

|

| The 1851 census - Samuel Swift as one of the butchers of Clare Market |

Charles Dickens (Jr.) in his

1879 Dictionary of London describes Clare Market as "

a market without a market-house; a collection of lanes, where every shop is tenanted by a butcher or greengrocer, and where the roadways are choked with costermongers' carts. To see Clare Market at its best, it is needful to go there on Saturday evening: then the narrow lanes are crowded, then the butchers' shops are ablaze with gas-lights flaring in the air, and the shouting of the salesman and costermonger is at its loudest ...

... nowhere in London is a poorer population to be found than that which is contained in the quadrangle formed by the Strand, Catherine-street, Long-acre, and Lincoln's-inn and the new law courts. The greater portion of those who are pushing through the crowd to make their purchases for tomorrow's dinner are women, and of them many have children in their arm ...

|

| Nowhere in London is a poorer population to be found ... (OS map 1895) |

... Ill-dressed, worn, untidy, and wretched, many of them look, but they joke with their acquaintances, and are keen hands at bargaining. Follow one, and look at the meat stall before which she steps. The shop is filled with strange pieces of coarse, dark-coloured, and unwholesome-looking meat. There is scarce a piece there whose form you recognise as familiar; no legs of mutton, no sirloins of beef, no chops or steaks, or ribs or shoulders. It is meat, and you take it on faith that it is meat of the ox or sheep; but beyond that you can say nothing".

So, when Samuel Crayden Swift set up his own premises in Battersea - and from there to South Kensington - he was also moving through the London classes as well, having started working amongst some of its very poorest.

His final home was at 95, Bolsover Street, near Fitzroy Square. Just as with his brother Edward Crayden, also in the 1870s, some of Samuel's extended family also lived with him. As well as Samuel Crayden and Mary Swift, the census record also lists two domestic servants, a journeyman butcher, his sister Ann (now Edmunds) and her husband and child, and another sister, Sarah Sands Swift, as a 'visitor'. But there's one more name that's of most interest to me - and that's Edward James Swift, my great-grandfather, listed as a 'butcher', learning his trade from his uncle.

10) Richard Foord Swift - struck off by the Freemasons

If this set of stories looks to be one of younger brothers doing increasingly better financially than their older brothers, that trend seems to come to a stop with the seventh son, Richard Foord Swift, the first son of Ann (Graves) Swift.

It seems Richard decided not to pursue the butcher's trade, even though he married the daughter of a Gravesend butcher, Sarah Ann Pearcey, in 1854. Instead, the 1855 Post Office Directory lists him as a 'grocer' living not far from his father-in-law's butchers premises, both in Gravesend (the same town that the eldest brother, John Crayden Swift, had moved to in the previous decade).

Richard Foord and Sarah Ann Swift then moves back to Sheppey where they have two children. They must then move again because, in 1865, Richard appears as a "Grocer and Tea Dealer" in the Register of the Pattison Lodge of the Freemasons in Plumstead, near Woolwich, Kent:

However, it obviously wasn't a ticket to success because, in 1868, Richard Foord is "struck-off for non-payment of dues". By April 1871, either Richard has died - which seems likely as there is no further trace of him, or the marriage has totally failed That's because by the 1871 census Sarah Ann is living with her son, Thomas, at her aunt's home while their daughter, Ann Eliza, is being looked after by her father.

The records show that, in 1881, Sarah Ann chose to emigrate with her daughter Ann Eliza to the United States. Ann Eliza marries a postal clerk, William Winchester in Bayonne, New Jersey. The 1910 US census shows Sarah Ann living with the Winchesters in Syracuse, New York state, where she dies in 1911.

Thomas, after first working in the West End, follows his sister and mother to the US, in 1882. He also marries in Bayonne, NJ, then lives with his family in Brooklyn, New York, before they move to California, where Thomas works as a Minister. He dies in 1930 in Los Angeles County - certainly a long way from the Isle of Sheppey!

11) George Graves Swift - and children who played in the same park as mine

The last of the sons, George Graves Swift, is also the last of this generation of Swift butchers. His marriage to Hannah Gorton in 1860, and the birthplaces of their six children, suggest they must have been living in and around Kensington for much of the next two decades. However, there's no clear record of George Graves until the 1881 census:

From 1881 to 1911, the census records list George as a butcher - or 'ex-butcher' - living in various addresses in Kensington, but all in a very short distance from each other. It's also clear that he was carrying on in the family trade here as well.

One of his sons, John Gorton Swift, took the butcher's trade on into the next generation. In another little quirk of the family tree, the 1901 census lists him as a "journeyman butcher" living with his family at 5, Maitland Road, Beckenham.

It's a house that looks out onto the slides and swings of Alexandra Recreation Ground, a park that I know very well because it's where my children used to play when they were growing up. No doubt John Gorton Swift's young children had done exactly the same, but a century earlier.

12) George Gorton - turning away from London and the Swifts

Having occasionally spilled over into the next generation in these tales, I'll finish with what the records show about another one of George Graves Swift's children - their eldest son, George. He led a very different life to his younger brother John Gorton Swift who, as outlined above, had stuck with the family butchers trade.

The tale needs to start with the mysterious gap in the census records for their father, George Graves Swift, between 1851 and 1881. Where was he to be found in the two intervening censuses and why was his wife, Hannah Swift, and three of their children, listed as living with Hannah's parents in Undy, Monmouthshire - without George Graves - in the 1871 census? There's no way of knowing fully, but, looking more closely, the eldest son George is listed as an "agricultural labourer" - so for him at least this is not just a temporary visit to Wales.

In fact, a closer look at Hannah's parents' record in the 1861 census shows that George was already living with his grandfather, listed as a shepherd, when he was only six:

Hannah, originally Hannah Gorton, had been brought up in rural Gloucestershire before moving, like so many others of her generation, to London. But it seems that George preferred to be away from life in the big city - in fact he also preferred to be known as George Gorton and not George Swift at all.

The 1881 census shows that George Gorton has married and is working as a storekeeper in the town of Newport; in 1891, George, his wife Emma and son, also George, have moved back to the Monmouthshire countryside where George (senior) is working as an agricultural labourer in the village of Llanvair Discoed, near Chepstow; in 1901 he's still in the same village but listed as a "miner in tunnel" - or "navvy" as one of the census administrators seems to have preferred as a description.

|

| The Gorton family in the 1901 census for Llanvair Discoed |

In the 1911 census, the last official record on George Gorton before he dies in 1920, he is listed as a 57 year-old "stone quarryman" in Caerwent, a village (and the site of the old Roman town) outside Chepstow - hard work for a man of that age.

|

| George and Emma Gorton in the 1911 census for Caerwent |

I'll let the final paragraph in this long post go forward yet one more generation - to George Gorton's son - also George - who was, of course, also Thomas Crayden Swift's great-grandson. He was listed in the 1901 census above as a blacksmith, and the 1939 census shows that he then became the 'village blacksmith' in Caerwent. But the corrections show that the census official has clearly struggled to get his name right! However, as his 1953 probate record also confirms, the correct form of his full name was George Crayden Gorton. So, right to the end of these tales, the Crayden name had not been forgotten after all!

Comments

Post a Comment