Transported for Life - the Lay of the Labourer

In November 1844, the campaigning London poet, Thomas Hood, wrote a story in his magazine entitled "The Lay of the Labourer". While the poem can be easily found online, it has taken a longer search to confirm that it forms part of a longer article written to campaign against the harsh sentence - of transportation for life to Australia - handed down to my ancestor, agricultural labourer Gifford White (my great-great-grandfather's brother).

Hood's article begins with a fictional story of him taking shelter in an alehouse that "had suffered from the hardness of the times":

"There will be a storm !” whispered Nature herself, as the crisp fallen leaves of autumn started up with a hollow rustle, and began dancing a wild round, with a whirlwind of dust, like some frantic orgy ushering in a revolution. ... At such times the proudest heads will bow to very low lintels; and setting dignity against a ducking, I very willingly condescended to stoop into “ The Plough.” ...

Ten or twelve men, some young, but the majority of the middle age, and one or two advanced in years, were seated at the sordid board. As many glasses and jugs of various patterns stood before them; but mostly empty, as was the tin tankard from which they had been replenished. ... Their coin and credit exhausted, they were keeping up the forms of drinking and good fellowship with plain water. ...

A glance sufficed to show that the company were of the labouring class - men with tanned, furrowed faces, and hairy freckled hands ... The topics, such as poor men discuss amongst themselves:- the dearness of bread, the shortness of work, the long hours of labour, the lowness of wages, the badness of the weather, the sickliness of the season, the signs of a hard winter, the general evils of want, poverty, and disease. ...

One of the elders, with a deep bass voice, and to a slow, sad air, began a song:

"A spade ! a rake ! a hoe ! A pickaxe or a bill !

A hook to reap or a scythe to mow,

A flail, or what ye will--

And here's the ready hand

To ply the needful land,

And skill'd enough, by lessons rough,

In Labour's rugged school ...

To Him who sends a drought

To parch the fields forlorn,

The rain to flood the meadows with mud.

The blight to blast the corn,

To Him I leave to guide

The bolt in its crooked path,

To strike the miser's rick and show

The skies blood-red with wrath ...

Ay, only give me work,

And then you need not fear

That I shall snare his Worship's hare,

Or kill his Grace's deer ;

Break into his lordship's house,

To steal the plate so rich ;

Or leave the yeoman that had a purse,

To welter in a ditch".

The poem also influenced Dickens, whose December 1844 story, 'The Chimes', references the 'rick-burning' that had become a form of protest in poverty-stricken rural areas, including Huntingdonshire, where Gifford White lived. In the story, an angry labourer exclaims: "There’ll be a Fire to-night ... There’ll be Fires this winter-time, to light the dark nights, East, West, North, and South. When you see the distant sky red, they’ll be blazing. When you see the distant sky red, think of me no more; or, if you do, remember what a Hell was lighted up inside of me, and think you see its flames reflected in the clouds".

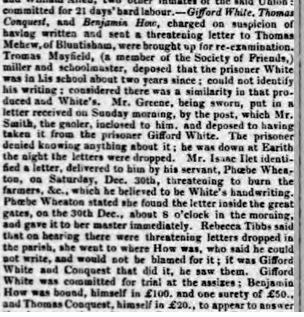

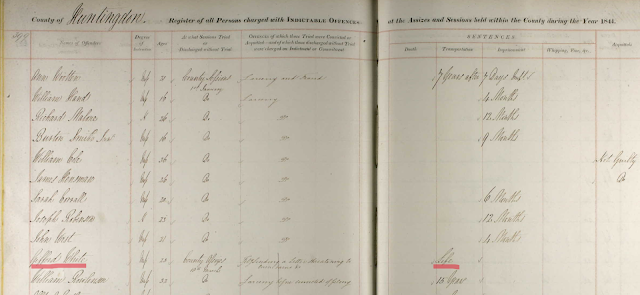

Hood's poem soon gained popularity, even finding its way to the pages of the 'South Australian' by March of the following year. But, it was to Australia that Gifford White was transported, having been found found guilty of "sending a letter threatening to burn farms" at the Huntingdon Assizes a year earlier, in March 1844.

|

| Hood's poem in the 'The South Australian' - March 1845 |

Hood's story is, as he says in his article, "Fiction" but, he adds, "a Fact and a Figure remain" - and that figure is Gifford White.

|

| A report of the trial from the Bury and Norwich Post, 1844 |

Hood explains 'the fact and the figure' as follows:

"For me, then, that doleful cry from the Starving Unemployed has no extrinsic horror; no peculiar pang, beyond that sympathetic one which must affect the species in general. Nevertheless, amidst the dismal chorus, one complaining voice rings distinctly on my inward ear; one melancholy Figure flits prominently before my mind's eye ... a real person, a living breathing man, with a known name. One whom I have never seen in the flesh; never spoken with; yet whose very words a still small voice is even now whispering to me, I know not whence, like the wind from a cloud. ... The Reader must judge: and when the case of my unknown, unconscious, invisible client shall be laid before him, will be able to say whether it required any unnatural sensitiveness of the system, any extraordinary softening of the heart or brain, to feel a strong human interest in the fate of Gifford White.

In the spring of the present year this very unfortunate and very young man was indicted, at the Huntingdon Assizes, for throwing the following letter, addressed externally and internally to the Farmers of Bluntisham, Hunts, into a strawyard :-

“ We are determined to set fire to the whole of this place, if you don't set us to work, and burn you in your beds, if there is not an alteration. What do you think the young men are to do if you don't set them to work? They must do something. The fact is, we cannot go on any longer. We must commit robbery, and every thing that is contrary to your wish. “I am, “ An Enemy.”

For this offence, admitted by his plea, the prisoner, aged eighteen, was sentenced, by a judge since deceased, to Transportation for Life!"

Hood goes on to doubt Gifford's guilt but argues that, at the very least, the sentence was excessive simply for allegedly making a 'threat', but one that was never carried out:

"A panic becomes a far more tragical affair when it arms one class of society against another; and instead of mere brutes and curs of low degree, animals of our own species are hunted down and hung, or at best, all but banished to another world, by transportation for life. It is difficult to believe that some such local panic did not influence the very severe sentence passed on Gifford White. Indeed the existence of something of the kind seems intimated by the judge himself, along with the extraordinary dictum that a verbal burn is worse than the actual cautery.

Lord Abinger said :- “ The offence was of a most atrocious character; and it might almost be said, that the sending of letters threatening to burn the property of the parties to whom they were addressed was worse than putting the threat into execution; for when a man lost his property by fire, he at least knew the worst of it, but he to whom such threats were made, was made to live in a state of continual terror and alarm.” ...

But, methinks I hear a voice say, it was necessary to make an example - a proceeding always accompanied by a certain degree of hardship, if not injustice, as regards the party selected to be punished in terrorem; unless the choice be made of a criminal especially deserving such a painful preference --- as for robbery with personal violence: whereas there appear to be no aggravations of the offence for which Gifford White was sentenced to a murderer's atonement. On the contrary, he pleaded guilty; a course generally admitted as an extenuation of guilt : his youth ought to have been a circumstance in his favour ; and, above all, the consideration that a threat does not necessarily involve the intent, much less the deed. ...

So clear a proof, to me, of the absence of any serious intent, or malice prepense, that the only agitation from the fall of such a missive in my farmyard, if I had one, would be the flutter amongst the poultry. At least theirs would be the only personal terror and alarm,- for, with other feelings, who could fail to be moved by a momentous question and declaration re-echoed by hundreds and thousands of able and willing but starving labourers. “What are we to do if you don't set us to work? We must do something. The fact is, we cannot go on any longer !" Can the wholesale emigration, so often proposed, be only transportation in disguise for using such language in common with Gifford White ?"

|

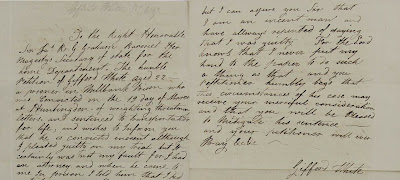

| 'Convict' Gifford White - "a sturdy good man" |

However, Hood's appeals were to no avail. Indeed, it seems an example was being made of Gifford White and perhaps the publicity his trial received helped set that example. Whether Gifford was indeed guilty of the charge, we will never know. A report from the Cambridge Independent Press shows that Gifford originally denied writing the letter but others claimed it was in his handwriting. At the trial, as Hood says, Gifford pleaded guilty but still received a sentence of transportation for life.

|

| Cambridge Independent Press Report, 1844 |

His relatives have a copy of a letter where Gifford appeals that he is innocent of the crime and had only pleaded guilty on the advice of his attorney.

Gifford White left Britain on the ship 'Hyderabad' in October 1844, arriving on Norfolk Island in February 1845. He was later moved on to Tasmania itself.

In fact, while Hood's story feared the worst for Gifford, my ancestor's actual life story doesn't finish anywhere near as badly. By 1856 he has been granted a conditional pardon and returned to Huntingdonshire to marry his wife Rebecca. They returned to Tasmania where Gifford made a successful life for himself as a shepherd and farmer ... but those details will need to be for another post.

Comments

Post a Comment