From Mariners to Mayors - getting rich from slavery in Liverpool

“Failure of a Gentleman”

Since childhood, I have understood that my Powell-Davies family surname originates from my adopted grandfather, Tom Davies, adding on the surname of his real mother, dairymaid Mary Powell. I’ve often wondered about the circumstances of her pregnancy and what injustice that single mother may have suffered.

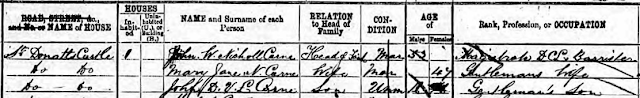

As I have explained in another post, family lore was that the ‘unknown’ father on Tom’s 1880 birth certificate was likely to be one of the sons of the landowner of the estate on which Mary worked. There’s good reason to suspect that the father was the eldest son, John Devereux Vann Loder Nicholl-Carne. He had been born into wealth in 1854, in Liverpool, but then brought up on the family estate near Bridgend in South Wales. The 1871 census lists him as a “gentleman’s son” living at St.Donat’s, a mediaeval castle bought by his father in the early 1860s.

It seems that John DVL Nicholl-Carne even managed to fail at being rich, the Cardiff Times of 1886 reporting on the “Failure of a Bridgend Gentleman” at the Cardiff Bankruptcy Court. “He borrowed to meet the expenses of a yacht … The yacht cost £5,000. He had never used it”... “He had failed to carry out any business, but had lived on an income derived from property in Liverpool, which came to him under his mother’s will”.

‘Brancker’, and some of the other names in the family tree, like ‘Aspinall’ and ‘Tobin’, will be immediately recognisable to those who have researched the history of the Liverpool slave trade. For example, they appear as the names of slave-owners in the database of the Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery (LBS). My personal ancestry research confirms both how marriage connections linked these families together, alongside their commercial links, and how, from relatively simple origins, some individuals amassed huge fortunes and influence, all thanks to the slave-trade and the later commerce built from it in Liverpool.

I’ll start by looking at the evidence in this family tree from the early eighteenth century. At that time, Liverpool was only just beginning to build its position in the North Atlantic slave trade, before becoming the slave-trading capital of Britain by the end of the century.

The three families – Brancker, Aspinall and Tobin – are represented in the family tree at the start of the century. However, to start with, there is no particular sign of great wealth.

Mary Jane’s great-grandfather, Thomas Brancker, born in 1715, had married Elizabeth Whitfield at St. Nicholas Church, Liverpool, in 1743. Thomas was a Liverpool apothecary, as shown by the 1750 baptism record of his son, Peter Whitfield Brancker.

However, it was his son, Peter Whitfield, that became wealthy from the slave trade, helped by a marriage into another family, the Aspinalls. Their clear and notorious links with the transportation of slaves are explained below.

The Aspinalls

James Aspinall (1729-1788), born in Liverpool, was the son of (confusingly) another James Aspinall (1702-1781), who was born in Melling (now in Sefton). The baptism record of the younger James Aspinall, in St Peter’s, Liverpool, appears to list the profession of his father (“James Aspenwell”) as “mariner”, linking him potentially to the start of slave-trading.

Distinguishing the two James Aspinalls from the records isn’t straightforward as the working lives of both will have overlapped. However, poll books and trade directories record one or the other of them as follows:

In April 1761, James Aspinwall is recorded as a plumber, working at the Old Dock.

In 1766, James Aspinall is listed as a plumber and glazier on South Side Old Dock. In 1774 and 1784, James Aspinall is listed as plumber / in the building trade, still on South Side Old Dock.

The baptism records for some of (the younger) James Aspinall’s children, also list his profession as ‘glazier’ (for his sons John Bridge Aspinall in 1759, William in 1761 and Thomas in 1765) and as ‘plumber’ at the Old Docks (in 1770 for his daughter Sarah).

So, certainly for the younger James Aspinall, the trades as listed, although based at the Docks, don’t automatically suggest a clear link with the slave trade. However, when he and his wife, Betty, are buried in St. George’s, Liverpool in 1788, his profession is clearly listed as ‘merchant’. But again, how can we tell what exactly the merchandise was?

The Zong massacre

The truth behind the ‘merchandise’ that James Aspinall was trading in has been exposed by the records of the ‘Zong massacre’ of 1781.

The LBS explains how “James Aspinall, along with William Gregson, John Gregson, James Gregson and Edward Wilson were the co-owners of the slave ship Zong, the subject of a famous legal action in 1781-3. Hundreds of enslaved people were thrown overboard in a voyage across the Atlantic when the ship ran low on drinking water. 232 of the 440 enslaved people who embarked on the voyage died before disembarkation at Black River, Jamaica. The ship's owners then claimed compensation from their insurers. The insurers refused to honour the claim. Judge Mansfield ruled that, although the ship's crew were found to be negligent, the enslaved people were to be treated like any other property and the ship's owners were acquitted of any liability”.

William Gregson, who led the syndicate that owned the Zong, may, like James Aspinall, have originally worked in trades linked to ships, in his case a ropemaker. However, he became, according to Wikipedia, “one of Britain's most prolific slave traders with at least 152 slave voyages recorded to his name … Gregson's vessels are recorded as having carried 58,201 Africans, of whom 9,148 died on board”. He amassed huge personal wealth and was also Mayor of Liverpool in 1762. This was the horrific trade the Aspinalls were engaged in too.

J & J Aspinall, slave traders

Martin Lynn in his “Trade and Politics in 19th century Liverpool” (1992) explains that the children of James Aspinall continued to build on their father’s slave-trading business.

Lynn writes that “the Aspinalls were prominent slave traders of Liverpool in the late eighteenth century with three members of the family, John, James and William, trading as J. and J. Aspinall. They traded with the Niger Delta and Angola; a further member of the family, Thomas, lived in Jamaica and was responsible for selling the slaves as they arrived from Africa. After 1807 they turned to 'legitimate' commerce and continued to trade until 1830”. This account is supported by the evidence in my family tree and ancestry records.

The eldest son, John Bridge Aspinall (1759-1830), is listed in the LBS records as a “Liverpool slave-trader and Mayor of Liverpool”. His portraits are no longer on display in the Walker Art Gallery because they have been “identified as having links to a person connected with transatlantic slavery”.

Yet his memorial plaque in Bath Abbey, where he is buried, sickeningly describes him as “beneficient to his fellow creatures and just to all”.

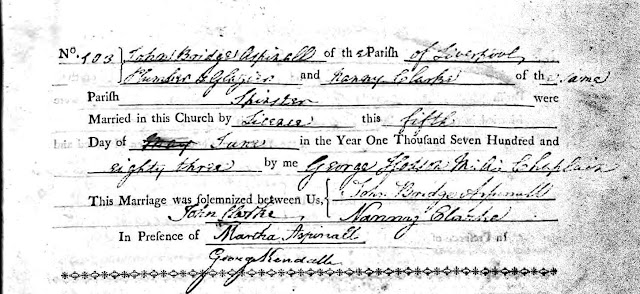

As with his father, John Bridge Aspinall's profession is first listed, in the record of his marriage in 1783, as ‘plumber and glazier’.

However, by 1806, having already been Mayor in 1803/4, he is listed in the poll records as an “esquire” living on Duke Street.

Gore’s Liverpool Directory of 1821 records John Aspinall as still residing at 106 Duke Street, but also lists the slave trading company recorded by Martin Lynn, as “John and James Aspinall”, merchants based at 24 Henry Street.

His trading partner and younger brother James Aspinall (1760-1814) is clearly listed in his daughter’s 1801 baptism record for St. George’s Liverpool as a “merchant”, with his wife Margaret also noted (originally Margaret Tobin, about who more is written below).

The further brother William Aspinall (1761-1816), recorded by Lynn as being part of the slave-trading company, is also confirmed in the family tree.

As Lynn suggests, ‘John and James Aspinall’ merchants is still operating in 1829, as shown in Gore’s Directory for that year, now from 25 Henry Street, Liverpool.

The Aspinalls in Jamaica

The fourth brother linked to the company, Thomas Aspinall (1765-1813), does indeed have family records showing he was based in Jamaica, just as Lynn suggests. These are records from the Jamaica C of E Parish Registers of the baptism of six of his children, between 1792 and 1807, in Kingston.

A mother is recorded in most of those records, named as Elizabeth Aspinall.

However, a marriage between Thomas and Elizabeth is not recorded until 1809, when they have returned to Liverpool (and before the birth of their last child Ellen Maria). In these records, Thomas is listed as a merchant. Elizabeth is listed but with an additional surname - as Elizabeth Aspinall Brown.These records match the LBS record for Thomas Aspinall, where he is described as a “slave-owner in Jamaica, slave-factor and merchant with Thomas Hardy in Kingston”. It adds that “the firm of Aspinall & Hardy, of Kingston, was heavily concerned in the slave trade by 1793 (in a typical advertisement the firm offered for sale in June 1783 “470 choice young Negroes upon the ship Elliott from Melinba Coast of Angola. Cargo all inoculated for the small-pox prior to leaving the coast and only has buried five during the voyage”) and afterwards did substantial business importing Irish linen, ham, butter, cheese, herrings etc from Liverpool”.

LBS suggest the children’s mother was a "free mulatto woman" and quotes from an 1812 report in the Royal Gazette of Jamaica of the marriage “some time since in England Thomas Aspinall esq, merchant formerly of this city but now of Liverpool, to Elizabeth Browne [sic] formerly of this island.” Her name presumably crudely reflected her mixed heritage.

LBS also describes how Thomas Aspinall left his house on Rodney Street in Liverpool to Elizabeth for life, together with an annuity of £600 p.a. in his will. These town houses on Rodney Street were built at the end of the eighteenth century for the wealthiest merchants. The street was named after Admiral Rodney, a supporter of the slave trade.

The next generation of Aspinalls

After the Slave Trade Act of 1807, families like the Aspinalls, that had made their fortunes from the slave-trade, were able to use their wealth to diverge into other activities. But, in addition, under the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833, “the British government raised £20 million to pay out for the loss of the slaves as business assets to the registered owners of the freed slaves. In 1833, £20 million amounted to 40% of the Treasury's annual income or approximately 5% of British GDP”.

One of the beneficiaries who was awarded ‘compensation’ under the Act was Liverpool ‘merchant’ Richard Addison, for his share of the Bath estate in Westmoreland Jamaica. However, Addison was also the son-in-law of John Bridge Aspinall, having married his daughter, Betty Aspinall, in 1812.

After Richard’s death, Betty is listed in the 1851 census as an “annuitant” living at Highfield in Rock Ferry. The census also lists her house servants and her son. The proceeds of the Aspinalls’ slave-trading were clearly being passed down through the family tree.

Another of the next generation of Aspinalls that can be traced in the ancestry records is Robert Augustus Aspinall (1807-1885), one of the sons born to Thomas and Elizabeth Aspinall in Jamaica. A picture of Robert can be found online.

You can judge whether the photo seems to show any traces of his mixed heritage. If there were, then Robert seems to have been at pains to distance himself from his past. The 1881 census lists his birthplace as Kingston – but the town in Surrey, not the one in Jamaica!

By 1881, Robert is a magistrate, living in the well-to-do Queensbury Place, Kensington, with a butler and servants. He died (after being run over by a cab!) in 1885 and is buried in Brompton Cemetery.

The Tobins

If you examine the family tree, you will see marriage links between the Aspinalls and another slave-trading family, the Tobins.

The first marriage between the families was between Margaret, who is recorded above as marrying the (third generation) James Aspinall. The marriage appears to have been around 1791.

Having been married to James when she was thirteen years younger than him, she easily outlived him and is recorded in the 1851 census as living as an ‘annuitant’ in one of the merchant town houses at 36 Rodney Street.

John Tobin – power and wealth built on slavery

From historical records, Margaret’s elder brother, Sir John Tobin (1763-1851), who also married into the Aspinall family, is very evidently an active participant and beneficiary from the slave-trade. He is listed in the LBS records as a “slave-trader, palm oil merchant and Mayor of Liverpool 1819-1820”. He was also knighted in 1820 as well.

Martin Lynn writes that “the Tobin family were originally from Dublin and derived from John Tobin, a periwig maker who moved to Douglas, Isle of Man. His son, Patrick Tobin (1735-94), founded the Tobin trading dynasty via the slave trade and the purchase of estates in the West Indies. He had seventeen children, of whom the most prominent were to be his eldest son, John Tobin (1763-1851), and his sixth, Thomas Tobin (1775-1863). John Tobin married Sarah Aspinall (1770-1853), daughter of John Aspinall of Liverpool, and they had eight children. This Aspinall connection was important to the Tobins and it is possible that Sarah brought money with her; certainly Tobin's business was transformed after his marriage in 1798”.

The family tree records confirm these origins, with John, like Margaret, being born on the Isle of Man. Their parents and grandparents records also support Lynn’s account, with his grandfather’s birth thought to be in Dublin in 1701.

Lynn explains that “John Tobin made his fortune with a number of successful transactions during the later years of the slave trade. He was a sailing master by the 1790s and … captain of a privateer out of Liverpool, the Gipsey, which in 1793 captured three French ships carrying a total of 484 slaves off the coast of Africa. By 1798 he was master of the Molly sailing to Angola for George Case & Co. of Liverpool, purchasing 436 slaves. By 1799, however, following his marriage, he was trading on his own account as John Tobin and Co.”LBS further records that Tobin “appears as Captain in 6 slaving voyages 1793-1803 and as owner in 10 slaving voyages 1794-1804, with William Aspinall in 7, with John Bridge Aspinall and James Aspinall and others (including Peter Whitfield Brancker in one) in 2, and with John Gladstone and others in one, in 1803, in which Tobin also appears as Captain”.

Gore’s Directory of 1796 records a Captain John Tobin of Duke Street, Liverpool.

In the record of his marriage to Sarah in 1798 at St. George’s, Liverpool, he is already described as a ‘gentleman’. However, Lynn is clear that this second marriage between the Tobin and Aspinall families was important for further advancing John Tobin’s fortunes.

The prospect of abolition obviously threatened the fortunes of slave traders like Tobin. However, they fought for ‘compensation’ and LBS records that, in 1835, Tobin, along with Peter Whitfield Brancker (more on the Branckers below), was awarded £875 under the Slavery Abolition Act for their ownership of the Cold Spring Plantation in Jamaica.

With his slavery profits threatened, as Martin Lynn notes, Tobin was instrumental in converting the trading links built through the slave-trade into an alternative trade in palm oil between Africa and Liverpool, from which he continued to amass even greater wealth. He was also part of a Tory elite that dominated Liverpool politics and Lynn comments that his election to Mayor in 1819 “may at least partly have been due to the sudden and unexpected rise in palm oil prices to record heights in 1818. Certainly, he needed the money. According to the Liverpool Mercury - his political opponents - he paid six shillings per vote to get elected in one of 'the most barefaced acts of bribery that ever disgraced even the electioneering annals of this venal rotten borough”.

The kind of wealth that Tobin’s trading activities – in slaves and palm oil, then also in railways and steamships – created, is illustrated by an article in the Penny Magazine of 1839 on the ‘Bedford Missal’, a beautifully illustrated mediaeval Book of Hours, now in the British Museum. The Magazine notes how it had been bought by Tobin at auction for £1100, after successfully outbidding others with various other ‘gentleman’ “for possession of the prize”.

He also had a mansion, Liscard Hall, built in Wallasey, and he and his wife are buried there, in what was St.John’s churchyard.

The Branckers

The last of the slave-trading families in the family tree are the Branckers, whose descendant Mary Jane Brancker married the Welsh landowner John Whitlock Nicholl Carne in 1844. As the family tree shows, Mary’s great-grandfather was the apothecary, Thomas Brancker, but her grandfather was another slave-trader, Peter Whitfield Brancker (1750-1836).

Peter Whitfield Brancker appears to have been another man able to advance himself through marriage into the slave-trading Aspinall family. In November 1782, he married Hannah Aspinall (1756-1814), the older sister of John Bridge Aspinall, at St. George’s in Liverpool.

Peter Whitfield Brancker’s profession is recorded simply as ‘mariner’ at the time of his marriage in 1782. This fits with the Liverpool Museums record of him being “originally a ship's captain. He was involved in nine voyages, transporting many enslaved African people to the Caribbean. From 1784 until 1799 he became a ship co-owner and merchant associated with 29 voyages to the Caribbean”.

Brancker’s advancement after his marriage to Hannah Aspinall isn’t just recorded in his ownership of slaving ships. By 1791 he is listed as a member of Liverpool’s Common Council, where he is understood to have objected to the abolition of the slave trade. He became Bailiff in 1795, and yet another of the slave-trading Mayors of Liverpool in 1801.

In Gore’s 1796 Directory, he is listed as a merchant based in Duke Street and Henry Street, streets where the Aspinalls and Tobins are also listed in later Directories.

As noted above, he was awarded, alongside John Tobin, ‘compensation’ under the Slavery Abolition Act for his ownership of the Cold Spring Plantation in Jamaica. However, while Tobin looked to now profit from palm oil, Brancker’s commercial interests turned to one of the products most closely associated with the slave-trade, sugar.

In the 1816 record of the birth of one of his sons, John Houghton, Brancker, now also another wealthy resident of Rodney Street, is now listed as a ‘sugar-refiner’.

Compiled a year before Peter Whitfield Brancker dies, a poll book for the 1835 Liverpool Town Election shows the old man supporting the three Tory candidates in St. Peter’s Ward, including one of the Tobins – but the Tories lost to the Whigs.

He was buried in St.James Garden Cemetery, Liverpool, close to the Anglican Cathedral.

Passing on the Brancker wealth

The LBS record for Peter Whitfield Brancker notes that his probate records for 1836 show he had amassed a personal estate of £25,000.

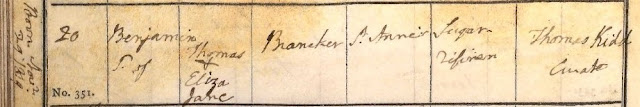

His eldest son, Thomas Brancker (1783 - 1853), inherited much of his father’s wealth, and also went into the sugar refining business, as confirmed by the birth records of his son, Benjamin, in 1819.

Thomas Brancker became another wealthy and influential individual, elected as Mayor of Liverpool in 1830, then knighted by George IV in 1831.

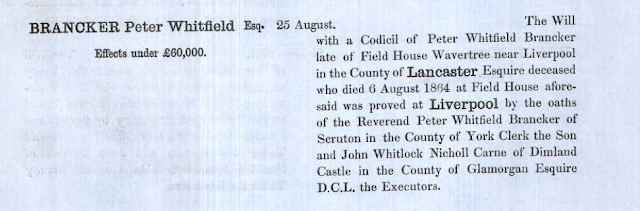

His second son, also Peter Whitfield Brancker (1786-1864), was Mary-Jane Brancker’s father. The LBS records suggest that he was also involved in his elder brother’s sugar refining business. This is supported by the 1834 electoral register that shows them both qualifying through their warehouses on North John Street.

In 1814, this second Peter Whitfield Brancker had married Elizabeth Houghton (1780-1853), the daughter of John Houghton, another ‘mariner’ according to their family records. It’s hard to avoid the suggestion that the Houghtons were also involved in slavery.

When the second Peter Whitfield Brancker died, in 1864, probate records show that his estate had “effects under £60,000” – nevertheless, a considerable sum. Both his son Reverend Peter Whitfield Brancker (the third) and daughter Mary Jane, through her husband, John Whitlock Nicholl Carne, are represented, listed as having sworn oaths.

So, this final link in the family tree hands on some of that wealth generated by slavery on to the Nicholl Carne family. Other descendants will have similar links too. I wonder quite how many of Britain’s wealthy families also sit in a family tree with roots in the horror of slavery?

Comments

Post a Comment