Gifford White - Life after 'transportation for life'

Transported from Bluntisham

A previous post on this blog explains how a young agricultural labourer, Gifford White, was sentenced to be transported for life from England. This post explains what befell of him once he boarded the convict ship Hyd(e)rabad in Woolwich in October 1844.

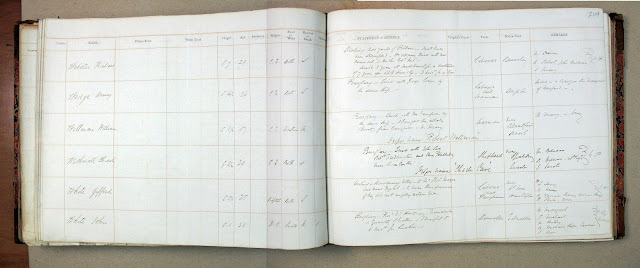

The ship's "indent", compiled to provide information on each convict on a ship's arrival, describes Gifford as a labourer and ploughman, 5' 51/2" tall, aged 25, a Baptist who can both read and write, guilty of "writing a threatening letter to Mr Thos. Mayer [Mahew] and Issac Eyelet - to burn their premises (?) if they did not employ certain men"

The final column lists his family as Father: Henry; Sisters: Phebe and Ann; Brothers: Daniel, Thomas, Henry and William (my grandmother's grandfather). And just to emphasise the local grievances that may have been behind his trial, the 1841 census lists both the Whites - a family of agricultural labourers - and Thomas Mahew - a farmer - on the same page, as neighbours in Wood End, in the small village of Bluntisham, Huntingdonshire:

The Surgeon's Journal

The surgeon's journal for the voyage can still be read online. In it, the surgeon J.O.McWilliam, states that the ship "having received on board two hundred and fifty male convicts at Woolwich dropped soon afterwards down to [the anchorage of] the Downs, whence she sailed for Norfolk Island on the morning of the 21st of October".

The ship sailed past Madeira on November 6th and around the cape of Good Hope on December 18th. After a stay at Simon's Bay [still a naval base today] the ship left on December 27th, arriving at Norfolk Island "with its characteristic pine forming its most prominent feature" on February 19th 1845. With the weather stormy, the ship waited off shore. "The following morning, a large flat bottomed boat came off the shore manned by convicts with a guard of soldiers of the 58th Regiment" to take the prisoners onto the island. [This journal matches with the records of the 58th (Rutlandshire) Regiment of Foot who were stationed on Norfolk Island in 1844].

The surgeon's comments in the Convict Records for the men on board the Hyderabad gives some insight into Gifford's character. He is described as being a "Steady Good Man". This appears to put him in the top category of the surgeon's standard descriptions, many others being just "Steady", "Good", "Fair" or "Indifferent".

Norfolk Island

So here is a man, being transported for life, nevertheless judged by the surgeon to be of good character. But what would Gifford have experienced when he arrived on the tiny, isolated Norfolk island?

The New South Wales Government archive explains how the island had been established as a penal establishment at the end of the previous century and had gained a reputation for being a place where convicts received "harsh punishments verging on the inhumane. It was not until Alexander Maconochie was appointed as Commandant of Norfolk Island in 1840 that the convicts started to be treated more humanely".

However, in February 1844, the year before the arrival of the Hyderabad, Maconochie was replaced by Joseph Childs with instructions to restore more severe discipline. His harsh regime provoked the 1846 "Cooking Pot Uprising" in 1846, although the men who arrived on the Hyderabad were not listed amongst its executed ringleaders. After this mutiny, Childs was replaced by a new Commandant, John Giles Price. Price, however, instituted an even tougher regime.

Although the writing is indistinct in places, Gifford's convict record shows that he was one of the many convicts who suffered under Price's harsh jurisdiction. His recorded offences while on Norfolk Island appear to include "Dereliction of Duty" in January 1847, to which he was sentenced to hard labour and, once again, "Neglect of Duty" in April 1847 where the punishment appears to be "hard labour in chains".

It is hard to know how trivial, or otherwise, this "neglect of duty" may have been but it is easy to imagine that such a regime would have broken some men either psychologically or physically - or both. Certainly, just amongst the Convict Records of those prisoners who sailed with Gifford on the Hyderabad, I have traced twenty-four men recorded as having died within ten years of their transportation - either at Norfolk Island or, after later being transferred to Tasmania, where many still worked under arduous conditions.

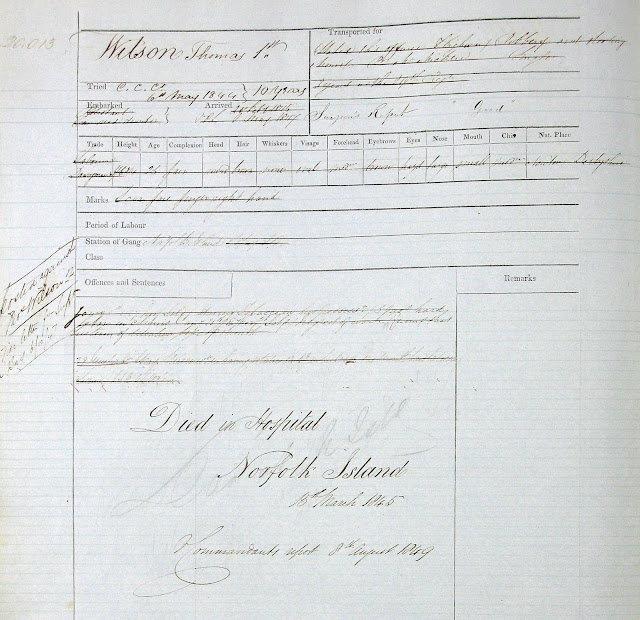

For example, the Convict Record of Thomas Wilson (below) records his death in the Hospital on Norfolk Island as early as March 1845 after what appears to be two periods of "hard labour in chains", one for "having tobacco in his possession".

Others I have traced as having died within ten years of their transportation are: James Eldredge ("Died on the Passage" - 1844), John Bowman (NI - 1845), William Hansford (NI - 1845), John Lovell (NI - 1845), George Pattison (NI - 1845), Amos Janes (NI - 1845), James Micklefield (NI - 1846), James Roberts (NI - 1846), John Sills (NI - 1846), Henry Harrison (NI - 1846), Thomas Hawe (1847 - Impression Bay), Charles Hiscocks (1847 - Impression Bay), Edward Preston (1848 - Imp. Bay), Richard Smout (Hobart - 1849), Charles Simmons (Hobart - 1849), Thomas McClocklin (1850 - Hobart), George Lowther (Bagdad - 1850), Alexander Rykind (Hobart - 1851), Samuel Pool (Hobart -1852), James Holbrook (Launceston - 1852), George Kennett (Launceston -1853), Thomas Holder (Ross - 1854), Charles Gomersall (Hobart - 1854).

Impression Bay was one of the many "probation stations" built under a Tasmania scheme that was designed to operate on a system of both reform and punishment. It seems that Gifford White, as a life-sentenced prisoner, would first have had to work at a penal settlement, others at a probation station like Impression Bay. As explained in a post on Tasmanian History, "If they progressed satisfactorily through several stages of decreasing severity, they received a probation pass and became available for hire to the settlers. ... Sustained good conduct eventually led to a ticket-of-leave or a pardon. ... In practice the scheme was a disastrous failure, undermined by poor planning and administration, inadequate funding, huge numbers, and an unforeseen economic depression".

Van Diemen's Land

In 1847, Gifford White was one of the men removed from Norfolk island and taken to "Van Diemen's Land" - modern-day Tasmania - on the ship 'Tory', arriving on 1 May 1847. However, Gifford was still a convict, with a 'life sentence' that meant he could not yet apply for a "Ticket of Leave", a form of parole that would at least allow him to live more freely. Indeed, one of the 'remarks' on his Convict Record from 1852 & 1853 confirms "not eligible for TL ... must serve 12 years from date of conviction".

His Convict Record therefore shows that Gifford, under the system outlined above, therefore became employed as a convict, with several different posts listed - but also endured further punishments too. For example, the record lists several different employers, particularly in Clarence Plains, but also a sentence of hard labour following "neglect of duty as watchman" in 1848, and it seems another sentence of hard labour in 1850. In 1851, while working for William Nichols in Clarence Plains, he also appears to have been reprimanded for disobeying orders.

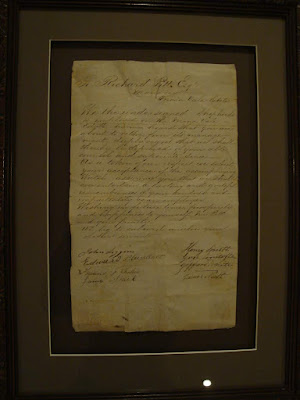

A surviving document shows him in the employment of James Collis in Black Brush in June 1849:

A Conditional Pardon - and a return to England

Finally, according to the Convict Record, Gifford White was successfully able to apply for a Ticket of Leave in October 1854 and then received his Conditional Pardon on July 22nd 1856.

In a book about the history of the area, "Cider Gums and Currawongs", its author, Gwen Hardstaff, writes that "Gifford White settled at Spitrock [probably Split Rock], a few kilometres south-west of the northern end of Great Lake, where Gifford was employed as a shepherd by Mr Alexander Reid of Ratho". While dates aren't given, since Alexander Reid (Senior), who developed Ratho Farm and its flock of Merino sheep, died in May 1858, this seems to have been where Gifford was working after he received his Ticket of Leave.

And it was after this date that Gifford White then left Tasmania for England. Whether, under the regulations, his Conditional Pardon fully entitled Gifford to do so seems less clear, but on 7 June 1858, the shipping records show that he arrived in Sydney on the 'Tasmania' from Hobart. From there, he must have taken a ship back to England.

How do we know for sure? Because on March 13th 1859, his marriage certificate shows that Gifford, recorded for the first time as a 'shepherd', is at the Baptist Chapel in Bluntisham, marrying a 23 year-old dressmaker from the village, Rebecca Shanks. This was the little girl, 15 years younger than Gifford, listed on the 1841 census above:

Just to provide further confirmation, in 1860, Rebecca is recorded as giving birth to their first daughter, Laura Selina White, on January 26th 1860, again in Bluntisham:

Just to provide further confirmation, in 1860, Rebecca is recorded as giving birth to their first daughter, Laura Selina White, on January 26th 1860, again in Bluntisham:

Returning to Tasmania

At some point after Laura Selina's birth, Gifford, already recorded as a shepherd in the Bluntisham documents above, returned to Tasmania, presumably to continue this employment. There's no clear record of how or when he travelled but, in August 1861, he is recorded as applying for two single "bounty tickets" for his wife and daughter to travel to Tasmania, at the cost of £10. His address is given as Bothwell:

These subsidised tickets were made available under various schemes during the nineteenth century to assist immigration to Tasmania, including to the wives and families of ticket-of-leave convicts in order to help build more stable communities. The scheme in operation under the 1858 regulations referred to above were as follows:

The book "Cider Gums and Currawongs", contains the following tale about Rebecca's arrival: "with their daughter, Selina, Rebecca travelled by coach from Hobart to Bothwell, before completing her journey to Spitrock on horseback. Although Rebecca had not much experience with horse riding, she soon learned, because this was the only means of transport to her new home".

|

| Tasmania in 1851 - map from the David Ramsey Map Collection |

A growing family - and a conflict over employer

After the hard times that Gifford had been through, hopefully he had finally found a life he could enjoy - although, as we shall see, perhaps it was not an easy life for the much younger Rebecca being thrown into such a new environment.

"Cider Gums and Currawongs" continues that "three more children were born while Rebecca was at Spitrock". They were Gifford (jnr) c.1863, Phoebe c.1867 and, between those two births, Thomas, for whom there is a confirmed birth date in the Australian records of January 17th 1865, in Bothwell.

However, not all was yet settled even for Gifford. The Tasmania crime records show that, on 19th December 1863, a warrant was issued for his arrest, "charged with a breach of the Masters and Servants Act in failing to enter upon the service of W.R. Allison Esquire as per agreement":

The Masters and Servants Acts were laws that sought to undermine trade union organisation in particular, forcing workers to stay with their contracted employer even if they were offered better pay and conditions elsewhere. And, in this case, it seems clear who was employing Gifford White: "Description: 50 years old (?), 5 feet 5 inches high, florid complexion; was formerly a constable, and is now employed as shepherd to Mr. Kermode, residing in the Great Lake Police District".

In January 1864, Gifford is further recorded as having been arrested by the Bothwell Municipal Police. Yet, it would seem, the situation was resolved - and, no doubt, due to some assistance from "Mr.Kermode", who clearly valued his work as a shepherd.

Luckily for Gifford, his new employer, Robert Quayle Kermode (1812-1870), was certainly a man of influence. A wealthy landowner, he was at that time completing the plans of his so-called "calendar house", built on his Mona Vale estate in Ross with 365 windows, reputedly then the largest private home ever built in Australia. In the biography accompanying the picture below, the Australian National Portrait gallery describe him as "a prominent anti-transportationist with liberal views ... a member of the [Tasmanian] Legislative Council and the House of Assembly in the 1850s and 1860s". Did Kermode perhaps feel he should look after his once transported shepherd? Perhaps even support him and his family in making another visit to England??

Another return to England

It seems all was not well with Rebecca. "Cider Gums and Currawongs" states that "during her fifth pregnancy, pining for her family and home in England, she became ill with a nervous disorder. Her doctor advised her to return home to England; she gave birth to her daughter Mary during the passage home".

However, while the book implies that Rebecca travelled without Gifford, the records for the sailing of the "Great Britain" from Victoria, Australia to Liverpool in March 1868 shows that the whole family travelled back to England together - the parents, three named children, and an infant, who would be Phoebe:

If Mary was born on the journey, then that wasn't how the birth was registered. Instead, the birth certificate shows the birth as being at at Bluntisham, on July 20th 1868:

It seems that the family also took the opportunity for the children to be baptised, probably as Baptists, certainly like their father. All the children are recorded as having been baptised on 13 September 1868, in Bluntisham cum Earith, in the England Christening Index.

But Gifford would need to return to his work in Tasmania. Once again, there isn't a clear record of a "Gifford White" returning without his family to Tasmania at this time. There is a passenger of this name arriving from Gravesend to Melbourne in November 1868 - but with an age given of 30. However, there is, once again, certainly a clear record of the "Bounty Tickets" Gifford then applied for from "Lake District Bothwell" - in February 1870 - for his wife and five children to return to Tasmania on the "Annesley":

There are also clear records of the passenger lists of the Annesley, showing the six passengers arriving in Launceston, via Melbourne, in October 1870:

|

Gifford's employer is clearly stated as being Mr. Kermode of Ross. The cost of the tickets - £52 - was also no small sum for a 'shepherd' to find - which suggests that either Gifford had already done well from his trade and saved wisely and/or perhaps that he was being financially supported in some way?

Gifford White - 'an intelligent man'

There are various unexpected sources that give some further insight into Gifford White's life from 1868 onwards.

Firstly, a 'Royal Commission on Fluke in Sheep' published in Tasmania in 1869 brought together evidence from over 150 farmers and landowners etc. The response from one of those witnesses, Mr H.M. Howells of Bothwell, lists the opinion of "Gifford White, an intelligent man, shepherd to Mr. Kermode". Clearly, Gifford had become a man whose opinions were respected by men in much greater positions of authority.

Secondly, the Museum at The Tasmanian Wool Centre in Ross has posted a picture of a letter that they hold, written about 1870, by eight shepherds on the Mona Vale Estate to its manager, Richard Pitt, on his retirement. Gifford White is one of those signatories:

Interestingly, the Museum's Facebook post of December 2020 writes that “unlike the other ‘shepherds of Mona Vale’ who signed Richard Pitt's retirement address, Gifford White became a landowner. He most likely rented a farm, saved his money, and perhaps with the help of a building society and his sons, bought a farm of 320 acres called ‘Brookdale’ in Bothwell”.

Finally, and really only for amusement, another Tasmania "Reports of Crime", now for September 1872, lists Gifford White as having been the victim of a crime, rather than a suspect. An interesting list of items (!) is given as having been stolen "from a hut at Silver Plains" [north of Bothwell] from Gifford White and William Cullingford.

Living on their own farm in Bothwell

The Wool Museum suggests that, at some point afterwards, the family were able to move from their isolated shepherd's home to 'Brookdale', a farm in Bothwell. Certainly in the Tasmania Directories of the 1890s, Gifford White is listed as a "farmer" in Bothwell - the profession also listed on his death certificate.

|

| 1892 Tasmania Directory |

After Gifford's death on May 2nd 1898, the Hobart Mercury records "Brookdale" as being his final residence where he died "in the 75th year of his age, after a long and painful illness borne with Christian fortitude". (His death certificate gives the first cause of death as 'malignant disease of the stomach' - the second, 'exhaustion').

|

| Gifford and Rebecca's gravestone in Bothwell |

Rebecca lived on until 1937, dying at the old age of 102, and both husband and wife are buried in Bothwell.

A local newspaper report recording Rebecca White reaching "the century" confirms the account of her life above, as well as adding some further detail about her first arrival in 1861: "From Hobart Mrs. White travelled to Bothwell by coach, and she rode from Bothwell to Split Rock, Great Lake, a distance of 43 miles on horseback, carrying a child in arms".

Their descendants, still living in Australia, have helped me with some of the research that has helped me to produce both my posts about the fascinating life of Gifford White, someone who endured where many others would not have.

Comments

Post a Comment